Sensitivity and vulnerability aren’t exactly embraced in our culture. This is changing a bit (shout out to Brene Brown) but traditionally, vulnerability has been considered a weakness. Rather than admit your feelings, flaws, and uncertainties, our culture glorifies indifference, arrogance, and overconfidence. As a writer, I used to approach my career this way.

Writing is filled with rejection, criticism, and uncertainty. You often feel like an imposter. Early in my career, another writer told me it was important to have “thick skin” because of this. Don’t take the criticism and rejection seriously, he said. Just ignore it and keep on trucking, he told me, because haters are gonna hate and you have to chase your dream and do what you love anyway. This was some of the worst writing advice I ever received.

Ignoring criticism, feedback, and failure means missing out on opportunities to get better. Thick skin suggests distance between the stimulus and your response. Instead of receiving the criticism or feedback, your skin is so thick that it doesn’t even register on your radar at all. It’s like tossing a pebble at a turtle. It bounces right off the turtle’s back, and the turtle has no idea it even happened. It’s why writers keep sending the same bad pitch to 50 media outlets, telling themselves it’s a “numbers game,” and eventually, someone will bite. It would be a better use of time to listen to the criticism, learn from the rejection, and hone the pitch accordingly.

I don’t suggest we all start crying in a fetal position anytime someone says the wrong thing or we feel a little stressed. But the concept of thick skin goes to the other extreme. Instead of figuring out how to deal with rejection, we choose to not let it get it to us at all. We’re supposed to be completely invulnerable to anything that doesn’t go our way, and that doesn’t solve anything, either. I’m not picking on other writers. I learned this the hard way – I cringe at some of the pitches I sent early in my freelancing career.

Let me offer a personal example to show you what productive vulnerability can look like in practice.

A few years ago, I wrote a book proposal and sent it to a high-profile agent. It’s always been my dream to write and publish a book, and I was excited to get this proposal in the hands of a big agent. She wrote back and, in so many words, told me she didn’t think I could write anything beyond a blog post.

Ouch! As a writer, I’ve dealt with a lot of rejection, but that stung. Hard. You’d have to have pretty thick skin to receive that kind of feedback and say, “This is fine.” And if you did, you’d probably be lying.

Thick skin is what people use to avoid damaging their delusions of grandeur. When you can accept that you may need improvement, the need to develop “thick skin” to protect yourself from criticism is pointless.

I was devastated, but I hearkened back to the advice every writer receives when they first start writing: GROW THICKER SKIN. A little thick-skinned jerkface in my head started screaming, Kristin, Man up! You’re a writer, you should be used to rejection. You can’t take it seriously. Move on! The jerk in my head didn’t just pull these cliches out of the air. It’s advice I’ve heard over and over throughout the years. If you want to be successful, you’re supposed to be impervious to negativity.

But then I had a thought: What if she’s right?

Might it be possible that this agent – who is a big deal and has enough experience to know what she’s talking about – could actually be onto something? And if she is, might it be possible for me to improve my writing and carry out my dream of publishing a book? I realized I had two options:

1. Let the feedback sink in and take advice from a professional, or

2. Ignore the rejection and keep sending out my proposal

The second option felt better, but deep down, I knew that it would only lead to more rejection. The first option took would be a lot more work, but I knew it would have a better chance of moving the needle. I took some time to sulk, then I re-read my proposal. And, you know? It wasn’t so good.

The clips I’d given the agent were short, matter-of-fact, and boring. They didn’t include examples of some of my meatier, reported writing. And my first chapter was super clunky, just awful. Most of it was copied and pasted from blog posts I’d written because I was in a hurry to get the proposal finished. But the hardest thing to admit was that even my best writing needed work. She was right. If I wanted to write a book, this proposal had to look like I could handle writing a book.

Truth hurts, and the truth was that it wasn’t a good proposal. Had I not allowed the criticism to get to me and sink deep into my bones, I wouldn’t have realized how utterly craptastic it was.

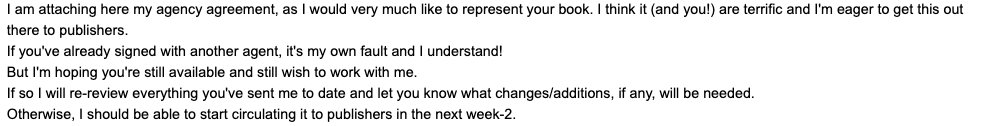

Armed with the painful truth, I sat down to rewrite. I purchased and read an entire book on how to write a proposal. I talked to other writers. I used better clips. I started my sample chapter from scratch. I tried to write with a book in mind, not a blog. When it was finally finished, I queried another agent. She had an excellent roster of clients and I really wanted to work with her. A few days later, she replied and asked to see my proposal. It wasn’t a done deal, but I hit send and crossed my fingers. Two months went by and I heard nothing, but one morning, as I was getting ready for a bike ride, I saw an email notification on my phone:

I couldn’t believe it. Everything else happened so fast: She asked me to update my proposal, I flew to New York to meet with a bunch of different publishers, my book went to auction, and next thing I knew, I was looking at my name on a cover at a Barnes & Noble.

After I told the story to a friend, she said, “I bet you want to shove it in that other agent’s face!” Absolutely not! If anything, I owe that agent. If it wasn’t for her criticism, and my sensitivity to it, I’d probably still be trying to sell the same poorly written proposal. Thick skin is what people use to avoid damaging their delusions of grandeur. When you can accept that you may need improvement, the need to develop “thick skin” to protect yourself from criticism is pointless.

We should recognize the value of sensitivity. The right amount of sensitivity to feedback and criticism is where the magic happens. You acknowledge your emotion, try to understand how, if at all, the feedback reflects on you, then use that to your advantage. Even if you’re not emotional about it, being sensitive to the feedback means you allow it to make an impression on you.

With thick skin, you miss out on opportunities to move ahead in your career. Of course, criticism and feedback can also be wrong. If you’re not sensitive, though, it’s harder to tell whether the criticism you’re getting is constructive or not. It rolls off your back by default, so you never have a chance to parse it.

For my entire career, I’ve focused on having thick skin and not allowing rejection to permeate me. It’s made me tenacious, I guess, but tenacity only takes you so far if you have a bad proposal on your hands. Rejection and criticism are made to be pesky roadblocks on the way to bigger and better things, but it would be a lot more productive if we thought of them as pit stops: places to reflect, recalibrate, and improve.